We can imagine a future where everyone can find and afford a quality home. Where every neighborhood offers a diversity of housing options. And where people up and down the income ladder can enjoy housing security and build wealth through ownership.

Achieving this vision requires more than incremental tinkering with today’s market institutions and public policies. It requires bold innovation by changemakers at all levels of government and in the private and nonprofit sectors.

The challenge is urgent. In many communities across the country, home prices and rents have climbed out of reach for a growing share of households. New construction disproportionately serves the affluent. Housing subsidies benefit only a fraction of those in need. Market pressures and gentrification are pushing people with lower incomes out of their communities. And America’s history of racial discrimination and segregation has locked too many out of neighborhoods of choice and created a widening homeownership gap between whites and people of color.

In the decades ahead, population growth, demographic change, and growing inequalities could worsen the mismatch between housing need and supply, further stretching family budgets, threatening people’s stability and the well-being of their children, and blocking opportunities for upward mobility. But we see reasons for optimism.

Housing: Promising Solutions

Across the country, changemakers in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors are exploring solutions to the complex housing challenges of today and tomorrow. Along the way, they are generating new insights and surfacing critical questions about what works. Below, we highlight four bold ideas that hold promise.

“Our city is growing very quickly right now… We have the ability to increase our housing supply. This plan certainly helps.”

— Jacob Frey, Mayor of Minneapolis, Minnesota, "Why Minneapolis Just Made Zoning History," CityLab

Produce more housing, more cheaply

In response to 21st century housing needs and preferences, mayors and local planners are modernizing local zoning and land use regulations so builders and developers can produce more housing at a lower cost. For instance, changemakers in

- Minneapolis recently eliminated all single-family zoning and allowed triplexes to be built anywhere in the city, and

- California passed sweeping legislation that fast-tracked projects with at least 50 percent affordable housing. Governor Gavin Newsom also signed an executive order to build affordable housing on excess state lands.

“Although zoning regulations don’t typically change dramatically from year to year, incremental changes in zoning add up.”

Meanwhile, private builders and developers are testing innovative design and construction techniques that reduce development costs and provide more diverse types of housing on less land. Examples include

- accessory dwelling units, which can increase rental options for people with low incomes in owner-occupied neighborhoods and provide multigenerational housing options for people who wish to grow old within a supportive community;

- pre-fabricated and modular units like the ones San Francisco’s Panoramic Interests produces for infill development on underused urban land; and

- design-build project delivery combined with new building technology to vertically integrate services, increase efficiency, and reduce construction costs, as demonstrated by companies like Blokable, Katerra, and Factory OS.

Blokable is a housing development company working to provide a “vertically integrated solution to create housing at scale.”

Preserve affordable housing and neighborhoods

Local housing officials are partnering with private-sector property owners and community-based nonprofits to preserve unsubsidized affordable housing that’s in short supply and at risk of disappearing. Potential solutions to save such housing are being explored in

- San Francisco and Oakland, where public funds acquire and renovate privately owned homes and apartments that serve families struggling financially;

- Minneapolis and Chicago, where philanthropy and lenders have established impact funds and loan products to preserve affordable rentals; and

- Minnesota, where local governments can provide tax breaks to landlords who agree to income and rent restrictions.

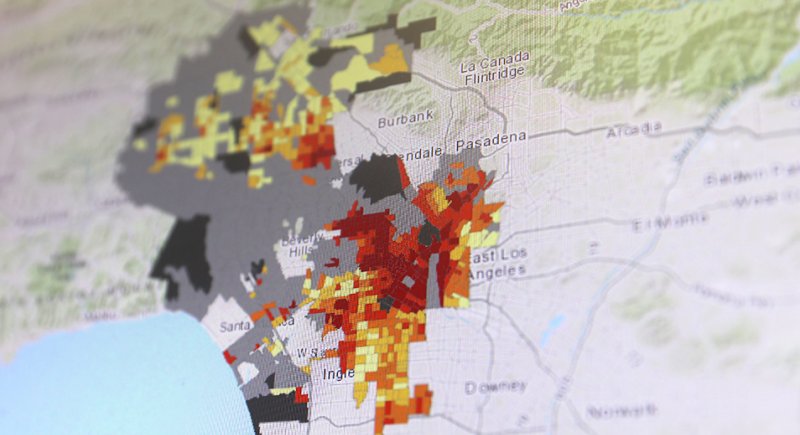

By tracking factors such as investments in transportation, changemakers in Los Angeles and elsewhere are predicting where displacement is likely to occur — and taking action.

At the same time, resident activists, community leaders, and city housing officials are testing strategies to prevent longtime residents from being displaced as neighborhoods gentrify. Efforts include

Right 2 Root

“It is often said that the people closest to a problem are closest to a solution ... The Right 2 Root campaign agrees.”

- community ownership models that keep land and housing affordable;

- Oakland’s “just cause eviction” ordinance, which protects tenants from arbitrary and discriminatory evictions;

- Washington, DC’s program to give tenants the first shot at purchasing their home when a landlord puts it up for sale; and

- the Right 2 Root campaign in Portland, which brings together neighborhood residents, businesses, and advocates to design plans for equitable and inclusive local development.

Expand housing assistance

Even if we remove barriers to producing or preserving housing in the private market, people at the bottom of the income ladder will still need reliable assistance to afford safe and stable housing. Possible solutions include

- boosting people’s incomes through a universal basic income or a substantially expanded earned income tax credit, like the renters’ tax credits offered by California and Maryland; and

- making the federal housing voucher program an entitlement that provides assistance to all families with incomes below a qualifying level.

“Divvy offers consumers the chance to live in a house they want even if they don’t have enough money to afford to buy it themselves, yet.”

Widen homeownership options

Some innovative leaders in the private and nonprofit sectors are exploring unconventional loan products that federal regulators and government-sponsored enterprises could assess and ultimately scale. These products could expand homeownership opportunities and close persistent gaps in home equity, particularly for people of color who have faced steep barriers to buying a home or sustaining homeownership. Among the possible solutions are

- rent-to-own agreements, offered by established companies like Home Partners of America and startups like Divvy and Ribbon. These agreements allow people who don’t qualify for a mortgage or can’t afford a down payment to rent a house, then buy it within a set time at a predetermined price;

- shared appreciation loans—which are being tested by companies like Landed, Point, and Unison—allow homebuyers to sell a percentage of their property (including future capital gains) to the lender in exchange for a reduced loan size; and

- small-dollar loans, which can help people with low and moderate incomes purchase lower-priced properties, including manufactured and modular homes.

VantageScore Solutions is offering a new credit scoring model that aims to benefit both lenders and consumers.

Financial technology, also known as fintech, has the potential to revolutionize underwriting and current appraisals processes, expanding access and reducing bias. For example,

- VantageScore and FICO are testing transaction data to build credit scores for consumers who previously had no or poor credit.

Housing: Knowledge Priorities

Based on conversations with an array of innovative thinkers and doers, we identified six priority areas where today’s policymakers, practitioners, market leaders, advocates, and philanthropists need better data and analysis to accelerate promising solutions to the country’s profound housing challenges.

“It would be a game-changer to have property data — a zoning score, all the information for developing a property — in a database, so that local institutions could price out development. This could develop a competitive market between mayors and local governments: City A has more potential for affordable housing; while City B is cheaper/easier to build in, for example.”

Unlock zoning data

Local and state planners working to ease regulatory constraints that limit housing supply and inflate housing costs lack information about how regulations differ across jurisdictions nationwide, how these differences affect housing availability and costs, and what reform strategies have increased housing supply. No national database exists on local land use regulations and zoning code; even when codes and regulations are published, they can be difficult to decipher and impossible to compare. If, however, planners and policymakers could compare regulations and their impacts across places and assess the effectiveness of reform strategies, they could prioritize local barriers to housing innovation and production. They also could implement models that work for peer communities. Achieving this would require

- “unlocking” foundational data on local land use regulations to create an open dataset of zoning restrictions across the US, as well as a database of major land use regulatory reforms and incentives;

- applying the data to develop new insights, toolkits, and data visualizations about regulatory impacts and reform options; and

- establishing a learning community of local practitioners who could guide the design and development of these resources, share best practices, and identify how zoning and land use reforms can help solve housing affordability challenges.

Understand NIMBY opposition

When mayors, housing officials, private developers, or nonprofit organizations try to expand the supply of housing where it’s needed most, they are often stymied by fierce “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) opposition. Many want to better understand what drives opposition to housing development so they can achieve consensus. For example, understanding the specific fears fueling NIMBY opposition in different communities could help local leaders and community members craft policies to protect against adverse outcomes—or marshal evidence that specific fears are unfounded. This knowledge-building could be advanced by

- using national zoning data (described above) to identify the characteristics of communities most likely to experience regulatory changes;

- monitoring shifts in housing availability, costs, and values over time and across communities with different zoning and regulatory regimes; and

- developing models that simulate the long-term market effects of new housing supply for people and communities, and that answer “what if” questions about the likely outcomes of zoning changes, increased density, or the development of more affordable housing options.

Monitor the affordable housing stock

Community-based organizations and local housing officials trying to preserve affordable housing urgently need real-time data and analytic tools to track unsubsidized affordable housing units and assess their risk of loss. Changemakers could then prioritize properties (and property owners) and target scarce resources to maintain the availability, quality, and affordability of this housing. Achieving this would require

- building inventories of unsubsidized housing and creating risk profiles for properties by mining public and private data sources;

- using such information to develop and test indicators that identify properties at greatest risk of being lost from the affordable stock; and

- evaluating policies that constrain or motivate property owners’ actions.

“Housing market trends are always one step ahead of the bureaucracy. That’s why mayors and governments need expert researchers to signal a loud warning that the market is heating up so we can fight displacement, and protect affordable housing, before it’s a problem.”

Develop early-warning indicators of displacement

Mayors and community development officials are looking for evidence-based early indicators of displacement and proven prevention strategies so they can effectively invest in housing affordability and protect residents before it’s too late. To predict displacement before it happens would require

- gathering and analyzing historical data about neighborhoods that have experienced displacement over the past decade;

- applying historical data to develop and test early-warning indicators of displacement;

- evaluating the effectiveness of approaches and investments to prevent displacement; and

- tracking the original residents of changing neighborhoods over time to observe the magnitude and consequences of displacement. This tracking could be beneficial to changemakers who want to demonstrate, with evidence, what happens to people uprooted from their neighborhoods.

Forecast housing assistance impacts

Low-income housing advocates arguing for increases in federal housing assistance are often dismissed because the cost to the federal budget is perceived as too high. Policymakers need compelling evidence about the long-term costs and benefits of alternative models for expanding housing assistance. With it, they could better assess the return on investment. Building this evidence would mean

- estimating the full costs and benefits of different approaches to housing assistance—including on homelessness, health, education, and economic development;

- launching demonstrations to test the impacts of various approaches; and

- developing new forecasting tools to answer “what if” questions about how alternative housing assistance policies would interact with changes in construction technologies, land use regulations, or mortgage financing.

“New developments at the federal level and new housing finance players have changed the market. More lenders are willing to incorporate nontraditional or alternative data to evaluate creditworthiness. Fintech firms are incorporating innovative approaches, and legacy institutions are exploring how to make use of these innovations. All these industry players have proprietary data, so you need to have collaboration if you want to move forward.”

Disentangle the racial homeownership gap

Private financial institutions, federal regulators, fair housing advocates, and local leaders experimenting with new financial products and tools don’t know what works to close persistent gaps in homeownership between white people and people of color. So far, their efforts have been stymied by the combination of enduring disparities in measurable factors—like incomes and credit scores—and factors that still have not been adequately measured or explained. They need help to disentangle key drivers of the racial homeownership gap and test the potential of products and tools for narrowing it. Building this knowledge would require

- assembling a storehouse of current and historical data to analyze factors supporting or undermining homeownership by race and ethnicity over time and across markets;

- developing metrics to quantify the gap in the homeownership rate and home equity, updating them regularly, and reporting them both locally and nationally;

- using the metrics to help predict the effects of proposed new policies and market innovations on people of color and on the homeownership gap; and

- supporting a peer learning network of local communities committed to narrowing the homeownership gap.

Based on the Housing Catalyst Brief written by, Margery Austin Turner, Solomon Greene, Corianne Payton Scally, Kathryn Reynolds, Jung Choi.